The Speleography of Great Salt Peter Cave

Reprinted from the September 1967 NSS News

Wayne R. White

NSS 8768

Eastern Kentucky University

Edited from a longer manuscript by H. L. Block

One of the best known of the many caves of Kentucky is Great Salt Peter Cave.

For several decades during the past and on into the present century, this cave

has been as well known as is Mammoth Cave. To the observant and inquisitive

speleologist the aura of many past eras is reflected in its passages.

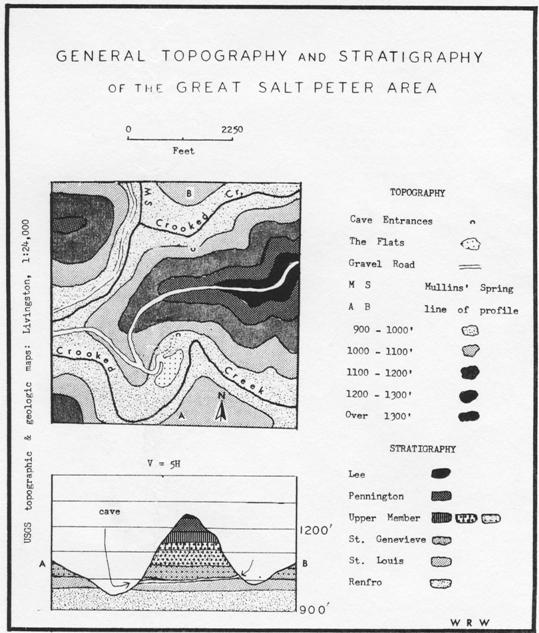

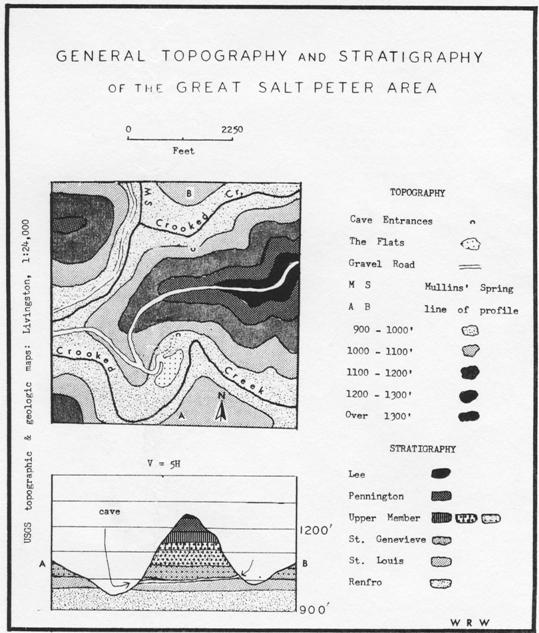

General Geology and Topography

Great Salt Peter Cave is located in the escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau

known to geographers as the Ridgetop and Limestone Valley Settlement Area and to

the geologists as the Eastern Kentucky Karst Region (see chart). The cave is in

the drainage of Crooked Creek, a tributary to the major regional stream,

Roundstone Creek. It is approximately thirty miles southeast of Richmond,

Kentucky. The USGS (1:24,000) Livingstone Quadrangle indicates the location of

the cave by name and symbol. A gravel road from State highway 1004 at Orlando

leads directly to the south entrance.

The Karst region is formed by an outcrop of Mississippian limestones which dip

gradually to the southeast where they are overlain by Pennsylvanian sands,

shales, and conglomerates, interspersed with a few thin coal seams. The

principal limestones, St. Genevieve and St. Louis, are the same as those in

which most of the caves of the western part of the state have been formed. The

Pennsylvanian materials, being highly resistant, are the major ridgetop formers

throughout the area and it is due to their occurrence and persistence that the

caves of the region still remain.

Regional relief throughout the general vicinity of the cave varies between 200

and 300 feet with ridgetops averaging about 1200 to 1300 feet above sea level.

Generally streams have eroded to the base of the Mississippian limestones and

several feet into the underlying shales at elevations of 900 to 1000 feet. The

greatest local relief occurs near the tops of ridges where the Pennsylvanian

conglomerate forms vertical bluffs up to seventy-five feet in height. Below the

conglomerate contact, the slope to the valley floors and streams is about twenty

degrees.

Most of the first-order streams of the area are ephemeral unless fed directly by

resurging waters. Crooked Creek, although apparently dry in late summer,

actually always carries water. The water usually accumulates in discontinuous

pools and/or moves slowly beneath alluvial sands and gravels of the creek bed.

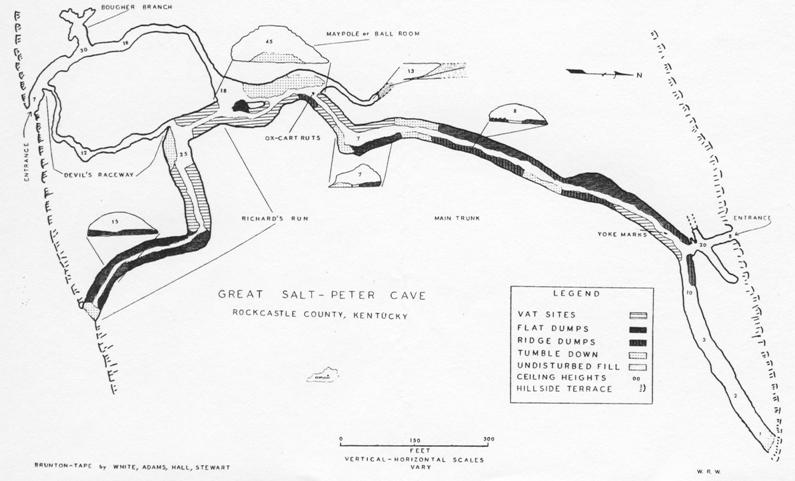

The Cave

Great Salt Peter Cave lies in the contact area of the St. Louis and St.

Genevieve limestones at an elevation of approximately 1000 feet, about 80 feet

above the bed of Crooked Creek. The cave has two entrances; the south entrance

is at an elevation of 980 feet, and the north at 1010 feet, at opposite sides of

the hill. The accompanying map of the cave shows prominent features and area

names.

Discovery and Exploration: 1799-1801

According to Brown, 1806, John Baker discovered and partially explored Great

Salt Peter Cave in 1799. When he discovered the cave, Baker proceeded only a

short distance into it; perhaps only through the twilight zone. The following

day he returned with his wife and two or three of their children. They entered

the cave through the north entrance; Baker carried a pine torch. After

penetrating several hundred yards, Baker became excited by the sound of a

"thundering torrent" and dropped the torch. The thunder was a 20-foot waterfall.

The torch was extinguished and the family, without flint and steel, was

enshrouded by the darkness. For about three days they wandered about in the

cave, fearful of approaching too close to the "torrent." It was finally Mrs.

Baker who "saw the light of day" and the family found their way out of the cave.

Ironically, had the Bakers approached to within 50 feet of the "frightening

torrent," they would have been able to see the south entrance.

Although no other references to exploration within the cave during this era were

found, one can conjecture that many other residents of the area explored the

cave. The cave is located near one of the better-traveled roads of that period

and so it was, after initial discovery, readily accessible.

First Period of Major Importance: 1801-1813

The events during this period projected Great Salt Peter into regional and

national importance. No longer was the cave just a hole in the ground. Great

Salt Peter Cave was to become one of the country's major resources. The whole

community adjacent to the cave was caught up and entwined in the economic and

military necessity of transforming the cave into its present state, which is as

much a manifestation of human endeavor as it is of natural processes of solution

and deposition.

With the shortage of gunpowder before and during the War of 1812, saltpeter was

extracted from the cave in large quantities. The manufacture of saltpeter on a

commercial basis began about 1801, increased until the year 1812, and began to

diminish immediately after. The method of manufacture, as reconstructed from

evidence in the cave, and from Brown, was in most instances similar to that used

elsewhere. Vats were constructed from easily available timber. The peterdirt was

dumped into the vats. Water poured through the dirt was subsequently drained

into a collection trough. The solution was carried outside the cave and boiled.

The sodium nitrate, the product of the leaching process, was then mixed with

ashes and altered to potassium nitrate, one of the ingredients of gunpowder.

On closer observation, however, there were several practices different from

those used in other manufacturing sites. The leaching vats were constructed of a

foundation of logs over which were placed wooden slabs about two inches thick.

On the slabs, wood shingles were fitted together to make the bottom of the vat

water tight. The sides of the vats were constructed from slabs about two to

three inches thick, fastened with pegs between four corner-post logs. The

average dimensions of the remaining vats are 38 inches high, 96 inches wide, and

84 inches deep. At the bottom and alongside of a series of adjacent vats was

built a collection trough. This trough was generally a log which had been split

and then hollowed out. The best preserved trough is 22 inches wide, 9 inches

deep, and 33 feet long. It served nine leaching vats.

According to Brown, the source of water for the leaching process during the

winter was the waterfall near the south entrance. The water was piped in through

logs. However, this source of water was apparently not sufficient during the

summer and water was brought to the vats from Crooked Creek. From the topography

of the area, it appears that it would have been more feasible to bring the

water, possibly by cart, from the nearest point of Crooked Creek into the cave

via the south entrance. Here the distance is slightly longer, but the slope is

significantly less than that of the north entrance. Also, no signs of a trail or

road exist on the north slope.

After one vat-full of dirt was thoroughly leached, the spent or sterile dirt was

removed from the vat and new dirt placed in it. After this process used all the

easily accessible dirt in the vicinity of the vats, and if the vats were still

useful, dirt was brought from other parts of the cave.

After a long period of use, the vats frequently became sufficiently

deteriorated, or the location of the new dirt was sufficiently distant from the

vat site, that new vats were constructed. The site of the old vats was generally

used as a dumping place for the spent dirt removed from the newer vats. By this

process of constructing and then abandoning vats as the peter-dirt supply

shifted, the manufacturing process migrated throughout the cave. However, the

migration was neither random nor haphazard. From the evidence in the cave, the

vats of this period were constructed in the sections of passages somewhat

removed from the major (south) entrance. The first vats were constructed either

in Richard's Run or in the northern end of the Main Trunk. Old vats are still

present in both of these sites, but buried beneath several feet of dumpings. As

the manufacturing process continued and the dirt in these sections was used, the

vat sites migrated toward the Maypole Room. The buried remains which are

farthest from the Maypole Room are generally the least preserved.

During the height of mining immediately before and during the War of 1812, there

were 60 to 70 men employed in the cave. Most of these laborers were people

living near the cave. Since this number of men would, at this early date,

represent a rather large portion of the total male labor force available, it is

quite possible that many of the traditional occupations of the region were

abandoned. Also taken out of the traditional economic system of the region were

large numbers of oxen, carts, and wagons which were used in the operation.

The oxen and vehicles were used to haul the new dirt to the vats and to haul the

spent dirt away from the leaching process. Collins describes the scene thus:

"Carts and wagons passed through (the cave) from one side of the mountain to the

other, without difficulty. The way is so level and straight, that oxen were soon

taught to pass through in perfect darkness, without a driver."

In several parts of the cave there is evidence of the passage of the oxen and

carts. The location of the best preserved tracks is indicated on the map. Also

visible in the place indicated on the map are stria caused by the yokes as the

oxen passed through a part of the cave with a five-feet high ceiling, the lowest

ceiling height in the main passage of the cave. At other parts of the Main Trunk

are pieces of breakdown which bear testimony to the iron-rimmed wheels which

passed over and left smoothed-out grooves as witness to their passage.

Other remnants of the mining are the dumps, which are indicated on the map. The

"ridge dumps" were undoubtedly produced by unloading two-wheeled carts by

allowing the weight of the load to tilt the cart backwards. The average volume

of these dumps is approximately one cubic yard. The flat-type dump was probably

produced by shoveling the dirt from four-wheeled wagons.

The source of light used by the miners was primarily pine torches and oil

burning lamps. Examples of the lamps are preserved in the museum of Renfro

Valley. Evidence of pine torches is preserved in the cave itself. Soot streaks

appear on the walls at intervals of approximately each fourth vat. The torches

were set in place either in man-made ledges or nooks, or naturally-occurring

nooks.

During this period, most of the saltpeter produced was shipped either to

Pittsburg or Lexington, Kentucky, by wagon and boat. As early as 1805, a "rather

large gunpowder mill" had been erected in Lexington. By 1810, there were 63

gunpowder mills in Kentucky which produced 115,716 pounds of powder from 201,937

pounds of saltpeter. Kentucky produced an even larger quantity in 1812, and on a

national scale was followed by Virginia with 48,175 pounds and Massachusetts

with 23,600 pounds. Following the War of 1812, the production of saltpeter from

the cave fell off sharply, continuing primarily in response to local and

regional demands.

Inter-War Period: 1815-1843

The events of the cave through this era are relatively obscure and appear to be

similar to those of the pre-1801 era. However, it seems plausible that the cave

did not lapse into complete obscurity or that it remained without visitors or

local producers of the saltpeter.

Period of the Mexican War: 1844-1848

Shortly before 1845, commercial working of the deposits of the cave commenced

anew: woodsmen felled trees for new vats, and for ashes; miners went to work

with pick, shovel, ox-cart, and lights. Again the cave began to hum with the

sounds of the mining activities.

During this period, however, the activities of the cave were not as important as

the 1812 era. Only a few men were employed and only a few oxen. From evidence

gleaned in the cave, there appears a distinct change in the method of vat

building. The new vats were constructed almost wholly from logs with no slabs,

even for the sides. This change in vat construction maybe interpreted in several

ways: 1) it might be due to an increased demand for saltpeter which required a

faster method of vat construction; or 2) it may have resulted from a shortage of

laborers for the hewing of logs into slabs. Whatever the major reason for

change, we do find a series of vats constructed in a radically different manner

from that of an earlier era.

Period of Local Function: 1850-1940

For approximately ninety years, only small amounts of saltpeter were mined. Even

though this interval includes the period of the Civil War, and several battles

were fought in the vicinity, very little attention was given to the cave as a

potential source of saltpeter. It was during this period the names Ball Room or

Maypole Room became attached to the largest chamber in the cave. During each

year, usually at spring planting, the residents of the region would forget many

of their common problems by celebrating the beginning of summer with an all-day

outing on the "flats" near the south entrance of the cave. Here the people would

gather, and bringing foods, beverages, and musical instruments, pass the day.

Two of the main events of this Summer Day Celebration took place in the Ball

Room. One was a dance in the southern end of the chamber. Here the passage is

relatively smooth and level and "fit for dancing." Another major event of the

day was the competition to climb the May Pole, a poplar sapling. The log was

trimmed of branches and peeled of its bark. The pole was placed in the large

chamber so that its upper end was jammed against the ceiling and the lower end

into the dirt floor. At the top of the pole was a dollar bill which belonged to

the first man to climb it.

The cave during this era was also a scene of two conflicting activities:

moonshining and religion. The major house of worship within the immediate

vicinity was a branch-and-vine-covered shelter of logs. On days of inclement

weather, the members of the congregation would meet in the Ball Room of the

cave. At several times during this era there was also moonshining activities

within the cave. According to the present residents of this area, the latest and

most popular site for the still and associated equipment was in the southern end

of the Main Trunk on the west side of the passage near the ceiling height figure

of "7." As a by-product, swine were brought into the cave and fattened on the

mash from the whiskey-making process.

It was during this era that many of the old vats were destroyed and were used

for firewood. During winter or rainy periods, those people who had not

accumulated a supply of wood stored in a dry place found a ready supply of

seasoned wood in the cave. During a span of several decades almost all of the

wood was removed from the cave.

Thus, although during this period the cave completely lapsed from national or

even state-wide attention, it was one of the dominant centers in the affairs of

the community. This era in the history of Great Salt Peter came to an abrupt end

with the transfer of ownership from Mrs. Morris, a widow, to John Lair, owner of

Renfro Valley.

The Period of Commercialization for Tourists: 1940-1943

In the early part of 1940, John Lair purchased the cave with the intention of

promoting it into a major tourist attraction of Kentucky. It was well known

throughout the state and is located only about eight miles from one of the major

north-south highways in the eastern part of the United States: Highway 25, the

Dixie Highway. Also, Renfro Valley, through its nationally-known Barn Dance,

fine cuisine, and museums, was a major tourist attraction which could be used to

attract attention to Great Salt Peter Cave.

The commercialization of the cave involved restoration of a few vats, a slight

leveling of the floor in a few places, and the placing of flagstones to form a

walkway from the road into the south entrance of the cave. Also a series of

steps was built from the main passage near the entrance to the Bougher Branch.

To bring attention to the cave, CBS radio made a nationwide broadcast from just

inside the south entrance on "opening night."

For several reasons the attractions of Great Salt Peter Cave were not

sufficiently strong to warrant a continuation of its activities on a commercial

basis. In 1943, the cave was abandoned commercially and again lapsed into

relative obscurity.

The Recent and Modern Period: 1943-1966

Though Mr. Lair did abandon the cave commercially, it was not abandoned by those

few who were attracted by its lure. Richard Mullins (Richard's Run) tells of

leading groups of people, mainly from southern Ohio and northern Kentucky,

through the cave almost every weekend. During the weekend of July 4, 1966, we

met approximately 60 people during the course of the afternoon inside and

outside the cave; the guide was Richard Mullins. It appears that the cave has

not completely lost its function nor has it lapsed into complete obscurity.

The State of Kentucky has expressed interest in the cave for making the area

into a State Historical Park and commercializing the cave. However, it is

obvious that permission from Mr. Lair would be needed and he has plans for again

commercializing the cave himself. In August 1966, a bulldozer was clearing the

trees and other vegetation from the edge of the "flats" to make a parking lot,

area for picnic tables, and recreational sites. Ideas and plans are being

discussed as to what renovations or restoration should be undertaken in the

cave. Although most of the plans have not been made public, it is apparent that

perhaps Great Salt Peter Cave is again awaiting for the resurgence of visitors

to view and recall these eras of its past.

Acknowledgements

Special acknowledgement is made to Professor William Adams for his assistance in

gathering the material for this paper. Also, appreciation is extended to Charles

R. Hall and Donald Stewart of Eastern Kentucky University and the Central

Kentucky Speleological Society, without whose aid this paper could not have been

completed.

References

Brown, Samuel. A Description of a Cave on Crooked Creek, with Remarks and

Observations on Nitre and Gun-Powder. This paper was read before the

Philosophical Society of Philadelphia on February 7, 1806. Dr. Brown was a

native of Lexington, Kentucky, and visited the cave several times between 1801

and 1806. A photostatic copy of the paper is in the library of The University of

Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

Collins, Lewis. History of Kentucky. No publisher given. Covington,

Kentucky, 1874. Especially relevant to this topic are pages 690-692.

Extant relevant records of Madison and Rockcastle Counties, Kentucky. Most of

the tax records of the 19th century were destroyed by fire. However, some

records were found which did mention the mining activity of the Great Salt Peter

Cave.

Maxson, Ralph Nelson. The Niter Caves of Kentucky. This paper read before

the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society, March 31,

1931. Original is in the library of The University of Kentucky.

Personal interviews with Mr. John Lair of Renfro Valley, Kentucky and with Mr.

Richard Mullins of Orlando, Kentucky.

Extensive field work by the author, William Adams, Charles Hall, and Don

Stewart.

<end>

Scanning and OCR work done by Andy Niekamp